The Striking Amaryllis Plant

The amaryllis plant is renowned for its striking beauty and dramatic presence, making it a favorite among garden enthusiasts and indoor plant lovers alike. Here are several aspects that contribute to its appeal:

Dazzling Flowers

Size and Shape: Amaryllis flowers are large and trumpet-shaped, typically ranging from 6 to 10 inches in diameter. They bloom on tall, sturdy stems that can reach up to 2 feet high.

Color Variety: The flowers come in a stunning array of colors, including vibrant reds, soft pinks, pure whites, and even bi-colored and patterned varieties. This wide range allows for stunning combinations and visual impact.

Blooms: Each bulb can produce multiple flowers, often accompanied by several stems, creating a lush floral display. The flowers can last for several weeks, bringing ongoing beauty to any space.

Lush Green Foliage

Bold Leaves: The amaryllis plant features long, strap-like leaves that can grow up to 2 feet in length. They are typically a rich, dark green, providing a beautiful backdrop to the vibrant blooms.

Architectural Form: The leaves emerge from the bulb in a graceful manner, adding to the plant’s overall stature and architectural beauty. The foliage remains lush and healthy, enhancing the plant’s overall appeal even after the flowers have faded.

Elegant Growth Habit

Imposing Presence: The height and bold structure of the amaryllis make it a standout plant. When in full bloom, it commands attention and can serve as a stunning focal point in any room or garden.

Versatility: Its versatility allows it to thrive in various settings, whether it be as a dramatic centerpiece on a dining table, an eye-catching feature on a windowsill, or a vibrant addition to outdoor landscaping.

Seasonal Charm

Winter Blooms: Amaryllis is often associated with the winter holiday season, bringing bursts of color and cheer during the colder months. Their ability to bloom indoors during this time enhances their desirability and beauty in festive decor.

Cyclical Beauty: The plant’s life cycle, from dormant bulb to radiantly blooming flower, adds a dynamic element to its beauty. Observing this transformation can be a rewarding experience.

Symbolic Beauty

Meanings and Associations: The amaryllis is often associated with pride, determination, and stunning beauty. These associations enhance its allure, as it carries not only aesthetic value but also emotional resonance.

In summary, the amaryllis plant captivates with its dramatic flowers, lush foliage, and imposing stature. Its vibrant colors and elegance shine, making it a cherished addition to both indoor and outdoor spaces. Whether blooming in solitude or as part of a stunning arrangement, the amaryllis undoubtedly brings beauty and joy to those who encounter it.

Content and imagery are AI-generated

Ecological Importance and Role of Small Oak Trees in Southeastern Pennsylvania

Small oak trees, often overlooked due to their small stature, play a significant and multi-faceted role in the ecosystems of southeastern Pennsylvania. Despite their size, these trees contribute greatly to biodiversity, forest health, and ecological stability. Here are several key aspects highlighting their ecological importance:

1. Habitat and Biodiversity Support

Tiny oak trees provide vital habitat and food sources for a variety of local wildlife. Their acorns are an essential food supply for mammals such as squirrels, deer, and chipmunks, as well as numerous bird species including jays, woodpeckers, and wild turkeys. Even at a young or small size, oak trees attract insects and bird species that depend on them for shelter and nesting locations.

The dense foliage and branches of these smaller oaks offer protective cover for smaller animals and birds, enhancing local biodiversity. In forest understories, they create microhabitats that support amphibians, pollinators, and beneficial fungi.

2. Soil Health and Nutrient Cycling

Tiny oak trees contribute to soil stabilization and nutrient cycling. Their root systems help bind soil, preventing erosion, especially on slopes and in riparian zones common in southeastern Pennsylvania. Leaf litter from oak trees enriches the soil with organic matter as it decomposes, fostering a rich ground layer for understory plants and microorganisms.

Additionally, the slow decomposition of oak leaves leads to the formation of humus, which improves soil structure and water retention. This is vital for supporting a healthy forest ecosystem and maintaining watershed quality.

3. Forest Succession and Regeneration

In natural forest succession, tiny oak trees represent the early and intermediate stages of oak community development. As saplings and young trees, they play a crucial role in regenerating oak populations after disturbances such as storms, fires, or human activity.

Their presence ensures the continuity of oak-dominated forests, which themselves are keystone communities within the region. Over time, these tiny trees grow and replace older or dying trees, maintaining forest canopy diversity and resilience.

4. Carbon Sequestration and Climate Regulation

Despite their small size compared to mature oaks, tiny oak trees contribute to carbon sequestration. As they photosynthesize, they capture and store carbon dioxide, helping mitigate the effects of climate change on a local scale. The collective presence of numerous young oaks in woodlands and urban green spaces adds up to a meaningful carbon sink.

Additionally, the shade provided by oak trees regulates microclimates, helping to moderate temperatures and maintain humidity in forested areas. This benefits not only plant species but also animal communities adapted to cooler, moist environments.

5. Indicators of Ecosystem Health

The health and presence of tiny oak trees can act as indicators of broader environmental conditions. Oaks are sensitive to changes in soil quality, air pollution, and water availability. A thriving population of young oaks suggests a stable ecosystem, whereas declines can signal problems such as habitat loss, invasive species pressure, or climate stress.

Content and imagery are AI generated

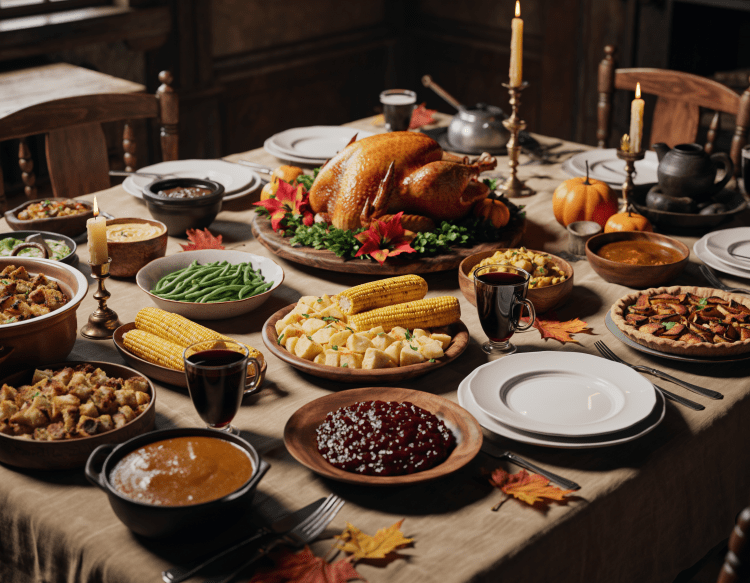

Thanksgiving Side Dishes

The original American Thanksgiving, celebrated in 1621 by the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag tribe, was a simple feast that marked a successful harvest and fostered a spirit of gratitude and cooperation. While modern Thanksgiving dinners may include an abundant array of dishes, the side dishes served at that first feast were quite different from the rich variety we see today. The original American Thanksgiving side dishes were based on what was locally available and rooted in the culinary traditions of both the Pilgrims and the Native Americans.

One of the key side dishes likely served at that first Thanksgiving was cornbread or some form of cornmeal-based bread. Corn was a staple crop for the Native Americans and was unfamiliar to the Pilgrims before their arrival. The Wampanoag taught them how to cultivate and cook corn, which became essential to their survival. Cornbread, made from ground corn mixed with water and cooked over an open flame, would have been a practical and nourishing accompaniment to the meal.

Another significant side dish was likely the “Three Sisters” vegetables—corn, beans, and squash—that were traditionally grown together by Native American farmers. Beans provided essential protein, squash offered variety and nutrition, and corn served as the carbohydrate base. These vegetables may have been roasted, boiled, or stewed, providing vital sustenance to the early settlers.

Wild greens and herbs were also likely part of the meal. Early American colonists and Native Americans would have gathered wild greens such as dandelion, chicory, and other native plants for freshness and nutrition. These greens may have been simply boiled or eaten raw, seasoned with local herbs.

Seafood was another dietary staple for the Pilgrims, given their proximity to the Atlantic coast. Clams, mussels, and fish might have been served as side dishes or as part of the main course. These provided a valuable source of protein alongside the turkey, which likely featured in the meal.

Unlike today’s Thanksgiving dinners, there were no mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce in its familiar form, or sweet potato casseroles with marshmallows. These dishes became popular much later as American culinary traditions evolved.

In summary, the original American Thanksgiving side dishes were simple, seasonal, and deeply influenced by Native American agricultural practices and ingredients readily available in the New World. Cornbread, the Three Sisters vegetables, wild greens, and seafood made up the delicious and practical side dishes that helped sustain the Pilgrims and created the foundation for what has become a cherished American tradition.

Copy and images generated by AI

Pumpkins as the Symbol of Halloween

The pumpkin is one of the most recognizable symbols of Halloween, instantly evoking images of glowing jack-o’-lanterns and autumn festivities. But how did this bright orange gourd become so closely associated with Halloween, a tradition with roots far beyond modern America? The answer lies in a mix of ancient folklore, immigrant customs, and agricultural abundance.

The origins of Halloween itself trace back to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, celebrated around October 31st. Samhain marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter. It was believed that on this night, the boundary between the living and the dead was blurred, allowing spirits to roam the earth. To ward off these spirits, the Celts carved faces into turnips, beets, or potatoes and illuminated them from inside with embers or candles. These early “jack-o’-lanterns” were meant to frighten away evil spirits or guide lost souls.

When Irish immigrants brought their Halloween traditions to North America in the 19th century, they found the native pumpkin, a squash native to the Americas, to be a perfect substitute for the turnip. Pumpkins were larger, easier to carve, and much more plentiful in the American autumn landscape. Over time, the pumpkin replaced the traditional root vegetables as the preferred medium for jack-o’-lanterns.

The transformation of the pumpkin into a Halloween icon also grew because of its strong ties to the fall harvest. Pumpkins are harvested in late September and October, making them a natural symbol of autumn and the seasonal bounty. This connection made pumpkins a popular decorative item for harvest festivals and celebrations, including Halloween.

Another key influence came from American popular culture. By the early 20th century, Halloween celebrations featuring carved pumpkins were widely documented in magazines, newspapers, and later in films. Children going door-to-door for “trick or treat” with pumpkin lanterns became an enduring image. The pumpkin also became associated with Halloween-themed stories and legends, further embedding it in the cultural landscape.

In conclusion, pumpkins became the symbol of Halloween through a combination of ancient Celtic customs adapted by Irish immigrants, the agricultural practicality of the pumpkin in America, and cultural reinforcement through popular media. This organic evolution helped carve the pumpkin’s iconic status as a symbol of Halloween, blending folklore, community tradition, and the vivid imagery of autumn harvest season. Today, nothing represents Halloween quite like a brightly glowing jack-o’-lantern crafted from a pumpkin.

Copy and images Created with AI

Migratory Birds from Southeastern PA

The migration of birds from Southeastern Pennsylvania is a remarkable natural phenomenon that reflects the incredible endurance and navigational skills of avian species. Each year, thousands of birds undertake long and often perilous journeys from this region as part of their seasonal migration patterns, driven by changes in climate, food availability, and breeding necessities.

Southeastern Pennsylvania, positioned along the Atlantic Flyway, serves as a critical corridor for many migratory birds traveling between their breeding grounds in the north and wintering habitats in the south. This flyway is a major north-south route that extends from the Arctic tundra down to the Caribbean and South America. The region’s geography, which includes a mix of forests, wetlands, and urban areas, provides essential stopover sites where birds can rest and refuel during their arduous trips.

The migration season in Southeastern Pennsylvania typically occurs during two peak times: in the spring, from March to May, when birds head north to breed, and in the fall, from August to November, when they travel south to escape the harsh winter conditions. During these periods, birdwatchers often observe a wide variety of species passing through or temporarily settling in the area. Common migratory birds include warblers, thrushes, hawks, and waterfowl such as ducks and geese.

Bird migration is primarily triggered by changes in daylight length and temperature, which signal birds to begin their travels. Many species rely on instinctual behaviors and environmental cues to navigate thousands of miles. Some use the position of the sun and stars, while others rely on the Earth’s magnetic field or landmarks. Southeastern Pennsylvania offers a diverse landscape that aids in navigation and provides necessary resources for migratory birds.

The importance of Southeastern Pennsylvania in bird migration also underscores the need for conservation efforts in the area. Urbanization, habitat loss, and pollution threaten the natural environments that these migratory birds depend on. Preserving green spaces, wetlands, and forested areas ensures that birds have safe places to rest and find food during their journey.

In conclusion, the migration of birds from Southeastern Pennsylvania represents a vital natural cycle that connects ecosystems across continents. Observing this migration provides insight into the resilience and adaptability of bird species while highlighting the importance of protecting their habitats to support continued biodiversity and ecological balance.

Copy and images Created with AI

POLLINATORS

Pollinators play a critical role in maintaining the health and vitality of ecosystems, particularly in regions like Southeast Pennsylvania. Their contributions encompass not only the production of food crops but also the overall biodiversity that sustains wildlife and plant populations.

One of the most significant aspects of pollinators is their role in food production. In Southeast Pennsylvania, many local farmers depend on pollinators such as bees, butterflies, and other insects to fertilize crops. Approximately one-third of the food we consume relies on pollination. Fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds are among the key crops that benefit from this process. For instance, species such as apples, strawberries, and blueberries are particularly dependent on pollinators. The local agricultural economy thrives due to the services that these insects provide, enhancing both food security and the livelihood of farmers.

Beyond agriculture, pollinators contribute to the health of natural ecosystems. They facilitate the reproduction of native plants, which in turn support wildlife. A diverse plant community provides habitat and food for various animals, from birds and mammals to insects. In Southeast Pennsylvania, native flowering plants like coneflowers and milkweeds are crucial for fostering robust ecosystems. When pollinators assist in the reproduction of these plants, they ensure the stability and resilience of local environments, promoting a balanced ecosystem.

Moreover, pollinators are key indicators of ecological health. A decline in pollinator populations can signify broader environmental issues, such as habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change. For instance, the decline of bees and other pollinators can lead to diminished plant diversity, which can have cascading effects throughout the food web. Monitoring pollinator populations can, therefore, provide essential insights into the overall condition of an ecosystem.

In Southeast Pennsylvania, the region’s rolling hills, diverse landscapes, and rich agricultural fields offer a variety of habitats for pollinators. However, urbanization and agricultural intensification pose significant threats to these vital creatures. Preserving pollinator habitats through the cultivation of native plants, reducing pesticide usage, and promoting organic practices can help mitigate these threats. Community efforts to establish pollinator gardens and promote awareness can further enhance the habitats available to these essential insects.

In conclusion, pollinators are indispensable to the ecosystem in Southeast Pennsylvania. Their contributions to food production, biodiversity, and environmental health underscore their importance. Protecting and supporting pollinator populations is not just an ecological necessity; it is vital for the sustainability of agriculture and the preservation of natural habitats. By fostering a pollinator-friendly environment, we can ensure the continued health and diversity of the ecosystems we value.

Copy and photo generated from Chat Unlimited AI

Top Five Perrenial Flowers

In Southeast Pennsylvania, spring is a vibrant time for gardeners and pollinators alike. Planting perennial flowers not only enhances the beauty of your garden but also supports local ecosystems by attracting essential pollinators such as bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. Here are five of the best perennial flowers for pollinators in this region:

1. Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)—The Purple Coneflower is a classic choice among gardeners and a favorite of pollinators. This hardy perennial produces striking, daisy-like flowers with prominent centers and pink to purple petals. Blooming from late spring into summer, Echinacea provides vital nectar for bees and butterflies. Additionally, its seeds are a food source for birds in the fall. Growing in well-drained soil and full sun, this plant thrives in various garden settings, including borders and meadows.

2. Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)—Black-eyed Susan is another native perennial that is excellent for attracting pollinators. With bright yellow petals and dark brown centers, these flowers create a cheerful display in gardens. They bloom from early summer to early fall, providing a long-lasting source of nectar for butterflies and bees. Black-eyed Susans are drought-tolerant and thrive in full sun, making them easy to maintain. They can be planted in clusters to create a stunning visual impact, while their seeds also attract birds later in the season.

3. Bee Balm (Monarda didyma)—Bee Balm, also known as Oswego tea, is particularly attractive to hummingbirds and bees due to its tubular flowers and fragrant leaves. This perennial blooms in various colors, including red, pink, and purple, from mid-summer to fall. Bee Balm thrives in moist, well-drained soils in full sun to partial shade, making it a versatile choice for different garden areas. Beyond its pollinator-friendly qualities, Bee Balm’s foliage can be used to make herbal tea, further adding to its appeal in the garden.

4. Phlox (Phlox paniculata)—Tall Phlox is a favorite among butterflies and bees, offering abundant nectar in its fragrant blooms from early summer to fall. Available in shades of pink, white, lavender, and purple, Phlox adds a splash of color to any garden. They prefer full sun and well-drained soil and can grow impressively tall, providing a lovely backdrop in borders or mixed flower beds. The dense clusters of flowers not only attract pollinators but also create a stunning visual effect.

5. Wild Indigo (Baptisia australis)—Wild Indigo is a lesser-known but highly beneficial perennial for pollinators. Its stunning, upright spikes of blue to violet flowers bloom in late spring to early summer, providing a rich source of nectar for various pollinators. This native plant is drought-resistant and thrives in full sun to partial shade, making it an excellent choice for low-maintenance gardens. Additionally, Wild Indigo has nitrogen-fixing properties, enriching the soil and benefiting surrounding plants.

Conclusion—Incorporating these five perennial flowers into your garden in Southeast Pennsylvania not only enhances its beauty but also plays a crucial role in supporting local pollinator populations. By choosing native and well-adapted plants, gardeners can create sustainable habitats that benefit both wildlife and the environment. Whether you have a large garden space or a small urban yard, these perennials are sure to attract and nourish a variety of pollinators throughout the spring and beyond.

Text and photos generated by AI

The Difference Between Irish Shamrocks and Four-Leaf Clovers

Even if you’ve never stepped foot on the Emerald Isle, you probably know the shamrock as a famous symbol of Ireland. For centuries, this herbaceous plant has been woven through stories about Saint Patrick, leprechauns, and other Irish tales. However, you may not know the differences between shamrocks and four-leaf clovers.

If you’re looking to understand more about these national symbols of Ireland, you’re in luck. This article will discuss the differences between shamrocks and clovers. We’ll also go over the history of each of these plants in Ireland.

Shamrocks vs Clovers

Now, shamrocks and clovers are both symbols of Ireland. They are also both used to symbolise good luck. However, there are a few differences between the two.

For starters, shamrocks always have three leaves, while clovers can have a fourth leaf. Shamrocks are usually green, but you can find purple, green or white clover. Finally, shamrocks grow in clumps, while four-leaf clovers are rare and grow one at a time.

Another difference between clovers and shamrocks is that four-leaf clovers are said to ward off evil spirits. Additionally, the clover’s four leaves represent luck, faith, hope, and love. On the other hand, shamrocks are known as symbols of the Holy Trinity: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Scientifically speaking, it can be tricky to pinpoint the difference between shamrocks and clovers. The genus Trifolium contains more than 300 species of clover. For example, white clover is Trifolium repens. Other plants like wood sorrel, or Oxalis acetosella, are sometimes referred to as clover.

The plants called shamrocks aren’t necessarily associated with a specific species name. The word shamrock stems from the Irish ‘seamrog’, which means little or young clover. The name shamrock can represent many species within the Trifolium genus, as long as they’re green and have three leaves. The most common species associated with the term shamrock is Trifolium dubium.

History of the Shamrock

The shamrock has been a symbol of Ireland for centuries, and there are many stories about the origins of this national icon. A popular legend says that Saint Patrick used the shamrock to explain the Holy Trinity to pagan Irish people.

Saint Patrick was a missionary credited with bringing Christianity to Ireland. He is also the patron saint of the country. The shamrock became associated with the Irish people and Saint Patrick after his time, and it has maintained its place in Irish culture ever since.

Today, the shamrock is often seen on St. Patrick’s Day. In Ireland, we celebrate St. Patrick’s Day by wearing green and attending festivals and parades. If you ever participate in these festivities, you’ll see shamrocks on flags, clothing, and decorations throughout the country.

History of the Irish Clover

The clover is also a symbol with a long history in Ireland. The druids are said to have believed clovers had magical powers. They used them in their ceremonies for their protective abilities.

The clover became associated with the Irish people after the druids were driven out of Ireland. It was seen as a lucky charm and often carried for protection or worn as a talisman.

Many associate clovers with another Irish symbol: the leprechaun. These are mischievous elves who enjoy playing tricks on humans. Stories often depict leprechauns wearing green clothes and hats adorned with four-leaf clovers.

Over the years, leprechauns became well-known creatures around the world. They’re found on many Irish products alongside the clover, including clothes, toys, and food.

Today, clover species grow on several continents across the globe. Children enjoy searching for four-leaf clovers while playing outside, while farmers and gardeners use clover as ground cover in their fields and gardens. Despite its wide use, this plant is still commonly associated with Ireland.

Article courtesy of Irish Family History Centre

Gardens Awaken

In late winter, the gardens of Southeast Pennsylvania begin to awaken from their winter slumber, signaling the imminent arrival of spring. This transitional period, typically characterized by February and early March, brings a subtle yet palpable shift in the landscape as nature starts to reassert itself.

One of the most noteworthy signs of late winter is the emergence of hardy perennial plants that are well-adapted to the region’s climate. The ground begins to thaw, enabling plants such as snowdrops (Galanthus), crocuses (Crocus), and early daffodils (Narcissus) to poke through the soil. These resilient flowers are often the first to bloom, providing bursts of color against the still-barren backdrop. Their early blooms not only bring joy to gardeners but also serve as essential food sources for pollinators, such as bees, which re-emerge as temperatures rise.

As temperatures slowly begin to warm, gardeners in Southeast Pennsylvania often take this opportunity to prepare their gardens for the upcoming growing season. This includes tasks like cleaning up debris left from the winter months, pruning dormant trees and shrubs, and amending garden beds. It’s a crucial time for planning and planting; gardeners may start sowing seeds of cold-tolerant crops like peas, kale, and spinach, which can thrive in the cooler soil conditions.

Additionally, many gardeners focus on the maintenance and repair of garden structures during this period. Raised beds may need reinforcing, and pathways could require attention to ensure they are navigable as the ground thaws. It’s essential to remove any remaining winter mulch that can inhibit early growth and to assess the health of perennials that have endured the winter chill.

Wildlife also becomes more active as late winter unfolds. Birds begin their migration back into the area, filling the air with their songs, while squirrels and other small mammals start foraging for food as their natural supplies dwindle. Gardeners often set out feeders to attract these creatures, enhancing the biodiversity of their gardens.

In summary, late winter in Southeast Pennsylvania is a time of awakening and preparation. As the ground thaws and the first blooms appear, gardeners and wildlife alike begin to stir with anticipation for the vibrant spring ahead. This crucial period sets the stage for the flourishing gardens that will soon follow, establishing a connection between the careful stewardship of humans and the resilience of nature.

Above copy generated by AI; photos in Adobe Firefly

90th Anniversary Gala Scholarship Fundraiser

The club’s March 26th meeting will see the return of “Black & White” fundraiser. Come join us as celebrate our 90th Anniversary in fashion! The $45 ticket price includes black and white decorated tables each with individual styles and themes, numerous raffle baskets, a catered hot luncheon, and a Martha Washington presentation by portrayer Alicia Dupuy.

Tickets—available to members as well as nonmembers—will be sold at the February meeting. Your paid entry ticket will be entered into the door prize drawing. Cash and/or checks accepted. No walk-ins allowed on the day of the event.

Unable to attend? You are encouraged to support the Martha Washington Garden Club scholarship fund by contributing a monetary donation, gift card, or a raffle basket. If possible, bring them to the February meeting. If you need a solicitation letter, they will be available at the February meeting.

Raffle tickets sold at the event will cost $5 for 7, or $10 for 15. All proceeds from the event go to the fund which offers scholarships to deserving students from our area pursuing careers in agriculture, horticulture, landscape architecture, sustainability, conservation, forestry or related subjects.

Winter Seed Sowing: A Guide to a Thriving Garden

Winter seed sowing is a method of planting seeds during the colder months that enables gardeners to take advantage of winter’s natural conditions to prepare for a fruitful spring. This technique, while not widely practiced, can significantly enhance the viability of plants, particularly hardy annuals, perennials, and certain vegetables.

Benefits of Winter Seed Sowing

One of the primary advantages of winter seed sowing is the stratification process that seeds undergo when exposed to cold temperatures. Many seeds require a period of cold to break dormancy and germinate successfully. By sowing seeds in winter, gardeners mimic the natural cycles that seeds would experience outdoors, enhancing germination rates and promoting robust early growth.

Additionally, sowing seeds in winter allows gardeners to get a head start on the growing season. By the time spring arrives, seedlings planted in winter will be well-established, giving them a competitive edge over those started later. This early sowing can lead to an earlier harvest, especially for fast-growing crops like lettuce, spinach, and peas.

The Process of Winter Seed Sowing

Choose the Right Seeds: Select hardy seeds such as pansies, snapdragons, or cool-season vegetables like kale and broccoli. Not all seeds benefit from winter sowing, so it’s important to conduct thorough research.

Prepare Containers: Use containers that allow for drainage, like seed trays, milk jugs, or plastic containers with holes at the bottom. Fill them with a quality seed-starting mix, ensuring it’s moist but not waterlogged.

Sow the Seeds: Plant the seeds according to the depth recommended on the seed packet. Cover them lightly with soil, and label each container for easy identification.

Water and Seal: Water the soil gently to ensure it’s humid. If using containers like milk jugs, you can leave them open for ventilation or seal them to create a mini-greenhouse effect, providing warmth while still allowing sunlight in.

Placement: Place the containers outdoors in an area that receives sunlight. Snow and cold temperatures help insulate the seeds, protecting them from extreme frost.

Monitor Growth: Check the moisture level periodically, ensuring the soil doesn’t dry out. As temperatures rise in early spring, watch for germination, and be prepared to transplant seedlings into your garden beds when they reach a suitable size.

Conclusion: Winter seed sowing is an innovative approach to gardening that can lead to a healthier and more productive garden. By using this technique, gardeners not only embrace the beauty of winter but also set the stage for a vibrant and thriving spring garden. Whether you’re a seasoned gardener or a beginner, winter seed sowing is worth considering for the upcoming growing season.

Be sure to attend the January 22, 2025 garden club meeting to watch member Jeanne Griffin discuss and demonstrate winter sowing in a milk jug. Members will learn how to plant seeds that will germinate over the winter and be ready to transplant in the spring. Everyone will take home seeds planted in a jug.

Article generated by AI. Photos of milk jugs with seedlings by Russ Hartman.